As designated environmental reporters in the 1970s and 80s, Howard, Israelson and Keating played a critical role in conveying information gathered from academics, scientists, governments and non-governmental organizations to the public.

“GLU's success was the care they took to be inclusive and democratic. I remember a lot of hard work that aimed for consensus on the principles that would guide campaign programs and actions each year.” — Sarah MillerIn the end, GLU adopted a compromise approach, supporting and facilitating the campaigns of local groups, while giving voice to those community concerns on the basin-wide international stage. In turn, the exuberance and local expertise of the grassroots groups kept GLU on the cutting edge of environmental developments. For example, GLU and its membership pioneered the ‘ecosystem approach’ and the ‘zero discharge’ goal. They insisted that Great Lakes governance needed to be guided by these concepts. As a result of the success of its community hearings on Great Lakes issues in 1986, GLU was granted official observer status during the formal negotiations between Canada and the U.S. on the 1987 update of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement (GLWQA). And when GLU talked, politicians listened because they knew the coalition was backed by hundreds of organizations with tens of thousands of members.

Mercury pollution in the English-Wabigoon river systemBy the late 1960s, the first concerns about mercury poisoning were being raised on the White Dog and Grassy Narrows reserves in Northwestern Ontario. Since 1962, up to 20 pounds a day of mercury had been dumped into the English-Wabigoon river system from a chlor-alkali plant operated by Reed Paper Limited (formerly the Dryden Chemical Company) to produce the chlorine used in bleaching pulp. While the province ordered the company to stop discharging mercury in March 1970 – and all commercial (but not sport) fishing in the river was banned – mercury releases persisted under various extensions granted to the company. Airborne emissions also continued until the company stopped using its mercury-based process in October 1975. By that time, the sub-acute symptoms of Minamata disease, a severe and irreversible neurological disorder, were being diagnosed among dozens of residents on the two reserves. Minamata is caused by high exposure to methyl-mercury, which bioaccumulated in the fish that comprised a large part of the diet on the reserves. When the company was sold in 1979, an estimated 16 tonnes of mercury remained in the river sediments, and mercury-related health problems are still being reported in the reserves to this day. |

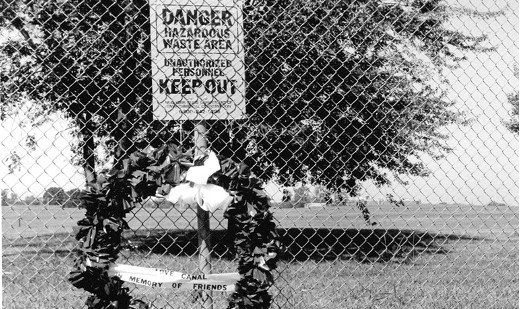

It was so dramatic. [The wastes in Love Canal] literally destroyed the neighbourhood ... [There were] swing sets, pools in the backyard – it could be your neighbourhood – literally melting in this toxic pool.On May 21, 1980, US President Jimmy Carter declared a federal health emergency and, in several phases, residents were evacuated from more than 900 homes in a 10-block area surrounding the canal. The notoriety of the Love Canal spurred the passage of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) in 1980 and the establishment of the Superfund remediation program which expanded to cover the excavation and containment of hazardous wastes leaking from hundreds of abandoned dump sites across the US. The Love Canal disposal site was covered by a synthetic liner and clay cap and surrounded by a barrier drainage system. Contamination from the site is still being controlled by a leachate collection and treatment facility. While the New York State Health Commissioner eventually allowed 250 of the abandoned homes to be resettled, hundreds more were demolished and a 16-hectare portion of the site remains empty and overgrown, locked behind security fences to this day. In September 2004, the Love Canal was removed from the Superfund’s National Priority List (NPL). Hyde Park, the “seeping giant” While the Love Canal got most of the headlines, Hooker Chemical continued to dump another 72,600 tonnes of chemical waste – four times more than what went into Love Canal – down the road into the six-hectare Hyde Park Landfill from 1953 to 1975. These were, primarily, chlorobenzenes, toluenes, halogenated aliphatics, and 2,4,5-trichlorophenol still bottoms. While all these compounds pose a serious threat to human health, the still bottoms were contaminated with up to 1.45 tonnes of dioxin, widely acknowledged as one of the most toxic chemicals known to science. That made Hyde Park the single largest deposit of dioxins in the world. And those dangerous chemical wastes were not staying put. Some 600 metres to the northeast of the site, the Niagara River flows north towards Lake Ontario, the primary source of drinking water for millions of people on both sides of the border. The ominously named Bloody Run Creek flowed through the landfill, then under a neighbouring industrial property and through a storm sewer that emptied into the Niagara Gorge. In addition, contaminated groundwater moved through both the glacial overburden and the heavily fractured dolomite bedrock outwards and downwards towards the Niagara Gorge. In 1979, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sued Hooker Chemical to force the company to remediate the site. Two Canadian environmental groups – Operation Clean Niagara and Pollution Probe, both represented by the Canadian Environmental Law Association (CELA) – intervened as amici curiae or “friends of the court” in the federal district court that hammered out and ratified the private settlement agreement between the company and the EPA in April 1982.

Hyde Park was just one [of hundreds of toxic waste sites in the Niagara Frontier], and perhaps one of the less really scary ones in a sense – it was in a hole in the ground and partly contained. There were others that were literally on the banks of the [Niagara] river.The Hyde Park site was listed on the NPL in September 1983. An aquifer survey, completed that year, defined the extent of contamination and a final remedial action plan was approved by the court in 1986. To date, a landfill cap installed in 1994 has decreased leachate generation, more than 1.1 million litres of dense oily liquids and some 23,000 cubic metres of contaminated sediment have been removed and treated, and purge wells have been installed to contain contaminant plumes and prevent wastes from seeping into the Niagara River. Operation and maintenance of the groundwater removal and treatment systems will continue for the next 30 years. The Hyde Park case sparked a lot of political interest at both the federal and provincial levels, as well as the development of some analytical tools still used today to track minute amounts of extremely toxic chemicals through the environment.

There was quite a mobilization of resources in Canada from a scientific and technical point of view. The Canada Centre for Inland Waters in Burlington … developed some really innovative research techniques for managing [tracking and monitoring] very small amounts of toxic chlorinated types of compounds.The Hyde Park Landfill file is still active Today, most of the chemical wastes buried across the Niagara Frontier are still lying in the ground, with the capacity to remain toxic for hundreds of years, if not forever. In September 2012, CELA on behalf of the cross-border environmental coalition Great Lakes United wrote to the Emergency and Remedial Response Division of the US EPA to oppose the deletion of the Hooker Hyde Park Superfund site from the National Priorities List. While deletion from the NPL does not preclude the EPA from conducting additional waste “removal” activities at the site, the Agency would be barred from conducting more extensive “remedial” activities, such as such as groundwater treatment. According to CELA counsel Joseph F. Castrilli, “Many of the key reasons that necessitated Hyde Park being listed on the NPL in the 1980s continue to exist today. The chemicals are still there, they are still hazardous and, because of the remedial action strategy chosen, they require robust environmental management essentially forever.” For those reasons, Great Lake United opposes the deletion of Hyde Park from the NPL.