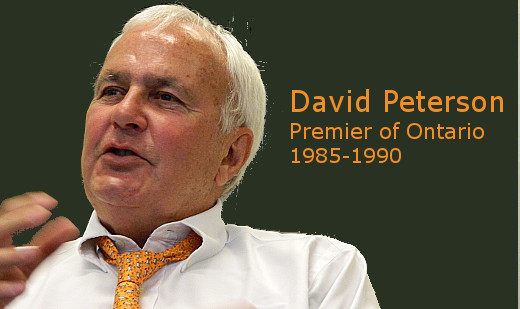

The 1980s was a decade of great change for environmentalism — around the world and very much so in Ontario. This became particularly evident after June 26, 1985, the day David Peterson was sworn in as Ontario’s 20th premier, leading the first Ontario Liberal government in 42 years.

For the next two years, Peterson led a minority government at Queen’s Park, under an unprecedented Accord reached with the opposition New Democratic Party. The Liberals actually had fewer seats (48 Liberal to 52 Conservative) than the Progressive Conservatives who had held power, but they managed to form a government with support from the NDP (who had 25 seats) under the accord, and took office with an ambitious program for environmental change.

By mid-1985 the environment had already become a top-of-mind issue for Ontarians. In the spring election campaign that led to his premiership, a spill of toxic PCBs from a truck on a northern Ontario road had become a major talking point. It escalated when a pregnant woman in a car behind the truck expressed concern; the Progressive Conservative environment minister quipped that she should not worry unless she was “a rat” licking the highway. The public was not amused and it became a significant election issue.

Ontario’s Environment — Under New Management

Peterson appointed Jim Bradley (MPP for St. Catharines, a seat he still holds), as Minister of the Environment. He also hired staff members who were committed to moving fast on the environmental issues of the day, including Mark Rudolph, David Oved and Gary Gallon. In his own office, Peterson hired Jan Whitelaw as a senior policy advisor.

Mark Rudolph had worked with the Liberals in opposition at Queen’s Park and as Chief of Staff to the federal environment minister (Charles Caccia) in Ottawa. Shortly after Rudolph joined Peterson’s government, he became Bradley’s chief of staff at the Ministry of the Environment. He worked closely with Gallon (who passed away in 2003), Bradley’s Senior Policy Advisor, also a Liberal staff member and a founder of Greenpeace. The office team was rounded out by David Oved, a former journalist who became Bradley’s press secretary, and Julia Langer who was the Junior Policy Advisor.

To say that there was good chemistry among the staff is perhaps an understatement — Rudolph and Whitelaw later married, had three boys and they still work together in the private sector on environmental issues.

Changes in the Environment

When Peterson came to power, some Ontarians were surprised at the speed of change in the environment file. As Peterson notes, for decades the Ontario Liberals were a small-c conservative party. He credits his predecessor, Stuart Smith (Liberal Party leader from 1976 to 1982), with moving the party forward, in part by hiring people like Rudolph and Gallon to work in the opposition.

To deliver their election promise of change, Peterson and Bradley moved fast. The budget for Ministry of the Environment more than doubled, from $300 million per year under the previous Progressive Conservative government to more than $700 million (by comparison, Ontario’s 2013-14 budget estimate for the Ministry of the Environment is $495 million).

Their staffers found that in addition to dealing with toxic spills, they had a ready-made list of big environmental issues to contend with right away. At the top of the list was acid rain (rain that turned acidic when combined with sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides). These two chemicals spewed from Ontario Hydro coal-burning power plants, Inco’s Sudbury nickel smelter and the tailpipes of cars and trucks across Ontario. Acid rain was killing lakes and trees ,threatened human health and had become a continent-sized pollution problem.

Determined to solve the issue, Peterson gave Bradley the okay to act quickly and bring in Countdown Acid Rain, an aggressive pollution reduction program. (The acid rain story is told in more detail elsewhere in this Beginnings series.) Vale Corp. (Inco’s successor in Sudbury), credits acid rain controls for giving the company the conditions to cut pollution by more than 90 per cent and make a profit by doing so.

Taking on the tough environmental issues

In the 1980s, Rudolph, Whitelaw, Gallon and others had to work tirelessly and seamlessly to negotiate with the polluters as their mandate from Peterson and Bradley was to hold firm to protect the environment Within six months of holding office, Peterson, Bradley and their team proclaimed a Spills Bill that could deal with incidents like the PCB spill (it had been passed by the previous government but never proclaimed as law) and took the steps that led to the world’s first Blue Box recycling program across Ontario.

The Peterson government also dealt with contentious issues that concerned people across Ontario, including a noxious pollution flowing into Lake Superior from a pulp and paper plant (then owned by Kimberly-Clark) at Terrace Bay, and pressure to log the old growth forests in Temagami, right next to a provincial park. They also implemented MISA (the Municipal/Industrial Strategy for Abatement – an industrial waterways clean-up program, Lifelines (a municipal water and sewage infrastructure enhancement program), an improved Parks Policy Book, and the start of the creation of the Rouge Park.

Nevertheless, the environmental philosophy of Rudolph, Whitelaw, Gallon and others — with backing by Peterson and Bradley — was to look at the bigger picture. It’s a philosophy that’s second nature to anyone who thinks seriously about the environment today, but it represented new thinking in the 80s.

They didn’t get everything done — for example, in opposition the Liberals had pushed for an environmental bill of rights (under which the Environmental Commissioner’s office was eventually established), but they never moved forward with the legislation during their time in office from 1985 to 1990. This was part of the “tradeoff” they undertook as they looked at the “bigger picture”.

Today, Peterson calls what his government achieved on the environment simply “doing a good job.” And Bradley, the longest serving MPP now at Queen’s Park (as of 2013), is still on the job, serving as environment minister again since 2011.