As designated environmental reporters in the 1970s and 80s, Howard, Israelson and Keating played a critical role in conveying information gathered from academics, scientists, governments and non-governmental organizations to the public.

“GLU's success was the care they took to be inclusive and democratic. I remember a lot of hard work that aimed for consensus on the principles that would guide campaign programs and actions each year.” — Sarah MillerIn the end, GLU adopted a compromise approach, supporting and facilitating the campaigns of local groups, while giving voice to those community concerns on the basin-wide international stage. In turn, the exuberance and local expertise of the grassroots groups kept GLU on the cutting edge of environmental developments. For example, GLU and its membership pioneered the ‘ecosystem approach’ and the ‘zero discharge’ goal. They insisted that Great Lakes governance needed to be guided by these concepts. As a result of the success of its community hearings on Great Lakes issues in 1986, GLU was granted official observer status during the formal negotiations between Canada and the U.S. on the 1987 update of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement (GLWQA). And when GLU talked, politicians listened because they knew the coalition was backed by hundreds of organizations with tens of thousands of members.

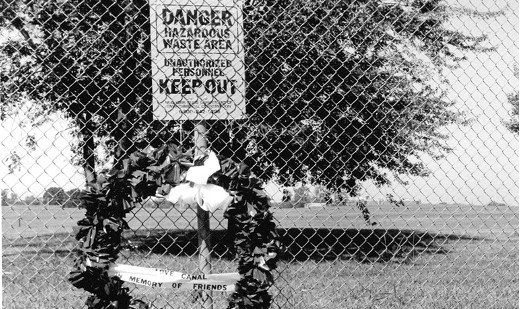

It was so dramatic. [The wastes in Love Canal] literally destroyed the neighbourhood ... [There were] swing sets, pools in the backyard – it could be your neighbourhood – literally melting in this toxic pool.On May 21, 1980, US President Jimmy Carter declared a federal health emergency and, in several phases, residents were evacuated from more than 900 homes in a 10-block area surrounding the canal. The notoriety of the Love Canal spurred the passage of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) in 1980 and the establishment of the Superfund remediation program which expanded to cover the excavation and containment of hazardous wastes leaking from hundreds of abandoned dump sites across the US. The Love Canal disposal site was covered by a synthetic liner and clay cap and surrounded by a barrier drainage system. Contamination from the site is still being controlled by a leachate collection and treatment facility. While the New York State Health Commissioner eventually allowed 250 of the abandoned homes to be resettled, hundreds more were demolished and a 16-hectare portion of the site remains empty and overgrown, locked behind security fences to this day. In September 2004, the Love Canal was removed from the Superfund’s National Priority List (NPL). Hyde Park, the “seeping giant” While the Love Canal got most of the headlines, Hooker Chemical continued to dump another 72,600 tonnes of chemical waste – four times more than what went into Love Canal – down the road into the six-hectare Hyde Park Landfill from 1953 to 1975. These were, primarily, chlorobenzenes, toluenes, halogenated aliphatics, and 2,4,5-trichlorophenol still bottoms. While all these compounds pose a serious threat to human health, the still bottoms were contaminated with up to 1.45 tonnes of dioxin, widely acknowledged as one of the most toxic chemicals known to science. That made Hyde Park the single largest deposit of dioxins in the world. And those dangerous chemical wastes were not staying put. Some 600 metres to the northeast of the site, the Niagara River flows north towards Lake Ontario, the primary source of drinking water for millions of people on both sides of the border. The ominously named Bloody Run Creek flowed through the landfill, then under a neighbouring industrial property and through a storm sewer that emptied into the Niagara Gorge. In addition, contaminated groundwater moved through both the glacial overburden and the heavily fractured dolomite bedrock outwards and downwards towards the Niagara Gorge. In 1979, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sued Hooker Chemical to force the company to remediate the site. Two Canadian environmental groups – Operation Clean Niagara and Pollution Probe, both represented by the Canadian Environmental Law Association (CELA) – intervened as amici curiae or “friends of the court” in the federal district court that hammered out and ratified the private settlement agreement between the company and the EPA in April 1982.

Hyde Park was just one [of hundreds of toxic waste sites in the Niagara Frontier], and perhaps one of the less really scary ones in a sense – it was in a hole in the ground and partly contained. There were others that were literally on the banks of the [Niagara] river.The Hyde Park site was listed on the NPL in September 1983. An aquifer survey, completed that year, defined the extent of contamination and a final remedial action plan was approved by the court in 1986. To date, a landfill cap installed in 1994 has decreased leachate generation, more than 1.1 million litres of dense oily liquids and some 23,000 cubic metres of contaminated sediment have been removed and treated, and purge wells have been installed to contain contaminant plumes and prevent wastes from seeping into the Niagara River. Operation and maintenance of the groundwater removal and treatment systems will continue for the next 30 years. The Hyde Park case sparked a lot of political interest at both the federal and provincial levels, as well as the development of some analytical tools still used today to track minute amounts of extremely toxic chemicals through the environment.

There was quite a mobilization of resources in Canada from a scientific and technical point of view. The Canada Centre for Inland Waters in Burlington … developed some really innovative research techniques for managing [tracking and monitoring] very small amounts of toxic chlorinated types of compounds.The Hyde Park Landfill file is still active Today, most of the chemical wastes buried across the Niagara Frontier are still lying in the ground, with the capacity to remain toxic for hundreds of years, if not forever. In September 2012, CELA on behalf of the cross-border environmental coalition Great Lakes United wrote to the Emergency and Remedial Response Division of the US EPA to oppose the deletion of the Hooker Hyde Park Superfund site from the National Priorities List. While deletion from the NPL does not preclude the EPA from conducting additional waste “removal” activities at the site, the Agency would be barred from conducting more extensive “remedial” activities, such as such as groundwater treatment. According to CELA counsel Joseph F. Castrilli, “Many of the key reasons that necessitated Hyde Park being listed on the NPL in the 1980s continue to exist today. The chemicals are still there, they are still hazardous and, because of the remedial action strategy chosen, they require robust environmental management essentially forever.” For those reasons, Great Lake United opposes the deletion of Hyde Park from the NPL.

[We had the idea that we] could use environmental laws to prevent pollution, to improve society and, to the extent that we had any environmental laws in those days, to try to enforce them.In those early, formative days of environmental law, long before provincial and federal governments would vow to get tough on polluters, CELA undertook the first prosecutions for noise pollution in Ontario, pushed for public consultation on the first certificates of approval, and rallied support for broader, more inclusive environmental legislation. CELA also attracted a roster of prominent lawyers from private practice, including a future member of the Supreme Court, who would volunteer to argue groundbreaking cases. Over the years, CELA has been instrumental in the development and passage of Ontario's Environmental Assessment Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, and the Environmental Bill of Rights. The association was also known for fighting and (mostly) winning a series of precedent-setting court cases. CELA lawyers

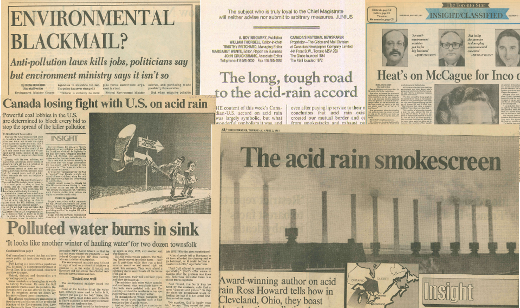

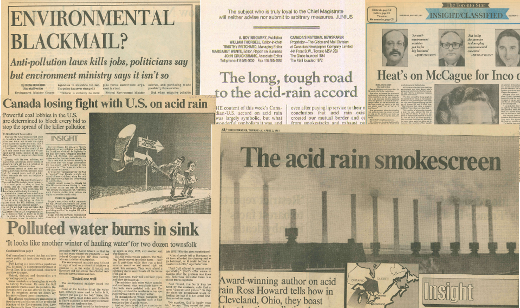

"Why don't you just go back up to Canada and tell your government that they'd better clean up its own act and then maybe...."It took 10 years for acid rain to become a household word. Acid rain became a prominent environmental issue after a Canadian study revealed that pollution causes acid rain, which damages the environment, which in turn threatens human health and quality of life. In 1980, Adele Hurley and Michael Perley founded the Canadian Coalition on Acid Rain to make this issue part of the political agenda in Canada and the United States. They first targeted Washington D.C., to persuade US senators to acknowledge that acid rain was an important issue and that a law should be passed should control air emissions. This is the story behind how the the United States' Environmental Protection Agency's Clean Air Act was passed. Listen to this story to learn about Michael Perley and Adele Hurley’s experiences along their journey to kill acid rain.