As designated environmental reporters in the 1970s and 80s, Howard, Israelson and Keating played a critical role in conveying information gathered from academics, scientists, governments and non-governmental organizations to the public.

Only by being knowledgeable of the history of the use and development of our forests and the landscape and soils on which they occur can we make intelligent decisions about their current and future development and uses.

I remember fights in [the district manager]'s office ... The door was closed and you'd hear screaming, then you'd hear things hit the wall. This was what it was like there. It was a circus.The Temagami story begins with Hap Wilson: canoeist, outfitter, artist, environment enthusiast, and author of many wilderness guidebooks. As a park ranger from 1976 to 1984, Wilson surveyed and published Temagami’s first, and very popular, Canoe Routes guidebook. This helped lead to a greater awareness of the need for wilderness protection, and opened up the area to outsiders who became advocates through discovery. However, logging and road building were still allowed. Things heated up when a district manager from MNR started illegally clearing land for the Red Squirrel Road in the fall of 1984. Hap was the first to learn about the road clearing, and quickly worked with his supervisor, Reg Sinclair from the Ministry of Natural Resources to "block" particular logging operations scheduled for critical areas by designing hiking trails or new canoe routespushing the development into the review process. In July of 1985, environmentalist Terry Grave and lawyer Owen Smith requested an Environmental Assessment (EA), and lobbied it hard through Queen’s Park for three months. In September 1985, the government finally agreed to conduct the EA. One year later, it was released, but the government had altered the document and removed the author’s name, making it unusable. Nevertheless, the EA was critical to delaying logging and building of the Red Squirrel Road, and gave time for Terry, Hap and activist Brian Back to get organized. In 1986, they formed the Temagami Wilderness Society, with the mission to keep Temagami wild. One of the first things the Society did was to identify a reason for preserving the wilderness in Temagami. In 1988, they commissioned Peter Quinby, a forest-ecology doctorate, to study the Temagami forest. Quinby confirmed the existence of old growth in Temagami – endangered from logging in Eastern Canada. With their cause strengthened by this finding, the Temagami Wilderness Society distributed brochures featuring photos of Temagami, brought people to the area, and campaigned to stop the area from being developed. For several years, the Temagami Wilderness Society did their best to stop the logging of old growth, working hard at public relations and fundraising. However, nothing seemed to stop those who were determined to build the road. In 1989, the government resumed building the Red Squirrel Road through the newly developed Lady Evelyn-Smoothwater Wilderness Park. Finally, the Society decided to set up a blockade at the Red Squirrel Road, the first of its kind in Eastern Canada. You can see the photos of the blockade in the photo section of this story. Today, Temagami is one of the remaining wilderness canoeing areas in the world, as logging and development continue to endanger these precious areas. In Ontario, we are lucky to have legislation and environmental groups to protect these precious landscapes and ecosystems. It is important for the next generation to keep it that way. Listen to the story to learn about the blockade, how Brian Back was buried in the ground, how former Ontario Premier Bob Rae (leader of the opposition at the time) was arrested, and learn what happened to Temagami and the Temagami Wilderness Society.

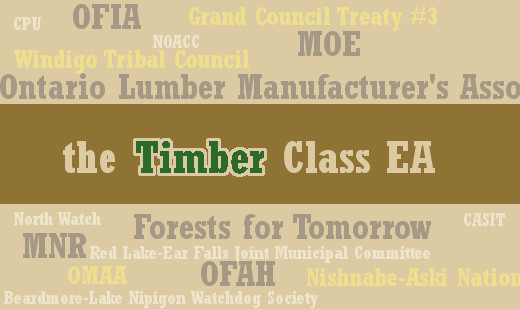

The Class EA process made us examine what MNR had done and made us improve what we were doing, and do all sorts of new things. - John CaryAt the time, public opposition was building against many of MNR’s proposed planning and forestry practices. This came to a head with protests against the Temagami Lake clear cuts and the Red Squirrel logging road. At the same time, a number of interest groups and public agencies were voicing concerns over the spraying of forest pesticides, the extent of allowable clear cuts, and even whether or not the Class EA was the right process for assessing the impacts of the province’s timber management policies. In December 1987, the Minister of the Environment sent MNR’s revised Class EA to hearings before the EA Board in order to ensure “full public participation in the decision-making process.” The Board was tasked with determining, first, whether to accept the Class EA, and second, whether to approve the timber management planning undertaking and, if so, what terms and conditions (if any) should be imposed.

Two important issues were restrictions on clear cut size, and the definition of forest management to be a more encompassing, more organic concept. - Anne KovenOver the 411 hearing days, the Board heard from more than 500 witnesses and amassed 70,000 pages of daily transcripts, more than 2,300 exhibits and tens of thousands of pages of supporting material. The final session concluded on November 12, 1992 in Sudbury, and the Board retired for more than 17 months to write its decision.

The decision revolutionized the forest industry, and led almost immediately to the Crown Forest Sustainability Act, which was a completely different philosophical approach to forest management. - Gord MillerUnfortunately, the interminable timber management hearing left the EA process with a nasty black eye. In its written decision, the Board complained that the “hearing was far too long and far too expensive.” MNR had completed only a small portion of its case when the hearing started – just four of the 17 witness panels – and the whole affair took on an overly legalistic and antagonistic air. As a result, the hearing was delayed for months while MNR completed its witness statements, procedural matters remained unsettled and, when it resumed, the cross-examination seemed endless. Even if everyone had cooperated fully, the hearing would still have lasted at least two years, but the Board complained that “the lawyers seemed more interested in strategies and tactics to fight one another than in concentrating on the evidence.”

The hearing had a deleterious effect on the EA process because it dragged on and on and on and on ... Any politician or any minister of the environment is going ‘EA is radioactive.’ - Don HuffThe scope of the case also put a tremendous strain on the intervenors, several of whom threatened to pull out after the first year if the province didn’t make additional funding available. While the province did increase funding, the Board later concluded in its decision that a “proponent should not have a bottomless pit of money with which to present its case and drag the hearing out, leaving other parties to participate on a shoestring.”

Certain public consultation mechanisms that the EA put in place ... are still extant and still working, that provide an opportunity to the local public, the regional public or anybody. - John CaryToday, the Forest Management Class EA is an “evergreen” Approval: MNR does not have to seek its renewal, but amendments must be made to ensure the Approval remains current. Like many other Class EAs, amendments can be requested at any time by members of the public, the proponent or other parties, and must be approved by Cabinet. This most recent series of amendments to the Class EA were adopted in 2007. In addition, MNR must prepare and submit to MOE a review of the Class EA planning process and its implementation of the conditions in the Approval every five years. The first of these was submitted in June 2009 and the next is due in June 2014. MNR is also required to submit to the Legislature a five-year State of the Forest Report, which was done in 2006 and 2012. However, much of the impact of the Timber Management Class EA decision could ultimately be undone by administrative tinkering that has occurred over the last decade. As part of MNR’s 2012 budget to improve ministry services while cutting costs, the government is considering amendments to the Crown Forest Sustainability Act, 1994. Among these, it could eliminate the requirement for forest management plans, extend forest resource licences indefinitely, and allow unlimited exemptions of forest operations from certain requirements of the Act. Only time will tell what the lasting impact of the landmark Class EA decision released nearly 20 years ago will be.