As designated environmental reporters in the 1970s and 80s, Howard, Israelson and Keating played a critical role in conveying information gathered from academics, scientists, governments and non-governmental organizations to the public.

Until the 1970s, “the practice of environmental law in the private sector was non-existent. There just wasn’t anything to support it.”Ontario’s Environmental Protection Act was enacted in 1971, followed by the Environmental Assessment Act in 1976, while Ottawa passed the Environmental Contaminants Act in 1975. Each of these new laws, and the regulations made under them, imposed stricter environmental responsibilities on Ontario’s resource companies, manufacturers, utilities and other private and public sector entities. These laws also contained enforcement powers and set fines and other penalties for polluters. However, prosecution was often the ‘last resort’ of the Ministry of Environment. Many of the early enforcement officers were drawn from the very industries they were hired to oversee. While they were able to negotiate some effective pollution reduction programs, the Ministry was not particularly aggressive in prosecuting companies or individuals that did not meet the province’s new environmental standards. Meanwhile, the public was growing more concerned about a host of emerging environmental problems: PCBs, acid rain, hazardous waste, lead smelters, dioxins and furans, mercury pollution, the “death” of Lake Erie, Love Canal … the list went on and on. As a result, federal and provincial regulators were soon forced to take a more proactive stance in the enforcement of the environmental rules. The Ontario Ministry of the Environment established its own Investigations and Enforcement Branch in 1985 to investigate major spills, hazwaste problems and industrial pollution, and to charge and prosecute those who broke the environmental law. Soon afterwards, a series of complex environmental assessments were launched for major projects proposed by the public sector, Crown corporations and municipalities. These twin developments made both industry and municipalities ‘sit up and pay attention.’ Once they understood the looming legal liabilities, they looked for their own environmental lawyers to explain their regulatory obligations and to defend their legal rights.

“There was a kind of an arc here [in the development of private environmental law practice]. There was the 70s when we were incubating ideas, through the gathering momentum of the early 80s, to the late 80s and early 90s when there was a very active [environmental] practice.” (Law Tape 2, 2:30-3:00)This new age of environmental law was interrupted temporarily by the economic downturn of the early to mid-1990s and the subsequent governmental response. . Some environmental programs were trimmed by cost-conscious governments in fear that such programs would drive business away. Major assessment hearings were cancelled in response to complaints about the cost and delay of environmental ‘red tape,’ and much of the intervenor funding that had sustained NGO participation was discontinued. While subsequent governments have showed a renewed enthusiasm for environmental initiatives, the 1970s and 80s marked the heyday of legal reform. At the same time, many technical concerns had devolved from lawyers to environmental engineers. These “qualified professionals” could guide clients through the increasingly complex world of environmental approvals, contaminated site remediation and regulatory compliance. Detailed and prescriptive environmental regulations, permit-by-rule systems and class environmental assessment processes spawned a whole new industry of environmental consultants who now handle much of the work that formerly went to law firms. Today, environmental law is firmly established as its own distinctive practice backed by a growing body of case law and precedents, and supported by an ever more complex regime of federal, provincial and municipal regulations, standards and by-laws. A number of Canadian universities offer environmental law programs, including York, Toronto, Dalhousie, Ottawa, Calgary and British Columbia. Both the Canadian and Ontario Bar Associations have established special sections to promote legal reform, professional development and education the areas of environmental, energy and resources law. Each federal, provincial and territorial environmental agency now maintains its own roster of environmental lawyers to handle prosecutions, support compliance, and draft acts, regulations, approvals and orders. For example, the Legal Services Branch of the Ontario Ministry of the Environment currently employs more than 50 lawyers, articling students and paralegals, constituting the largest single team of environmental lawyers in Canada. Most large law firms have environmental specialists on staff, while some lawyers have set up ‘boutique’ environmental law firms that may also cover related disciplines, like Aboriginal, energy, resource development and real estate law. Finally, a handful of environmental lawyers work with environmental and First Nations groups, residents associations and individuals to advocate regulatory amendments, undertake private prosecutions, and enable client participation in natural resource and land development approval processes.

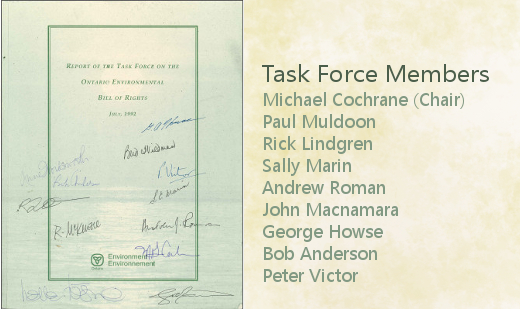

[We had the idea that we] could use environmental laws to prevent pollution, to improve society and, to the extent that we had any environmental laws in those days, to try to enforce them.In those early, formative days of environmental law, long before provincial and federal governments would vow to get tough on polluters, CELA undertook the first prosecutions for noise pollution in Ontario, pushed for public consultation on the first certificates of approval, and rallied support for broader, more inclusive environmental legislation. CELA also attracted a roster of prominent lawyers from private practice, including a future member of the Supreme Court, who would volunteer to argue groundbreaking cases. Over the years, CELA has been instrumental in the development and passage of Ontario's Environmental Assessment Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, and the Environmental Bill of Rights. The association was also known for fighting and (mostly) winning a series of precedent-setting court cases. CELA lawyers