How do you become an environmental lawyer when there are few environmental laws and almost no courses to prepare you?

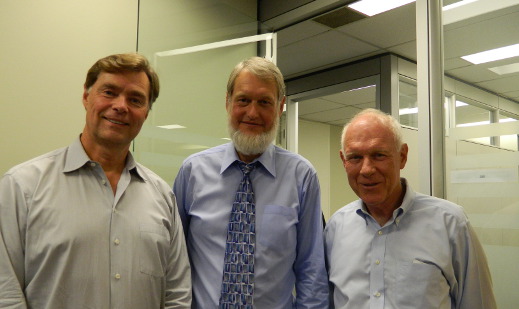

How do you become an environmental lawyer when there are few environmental laws and almost no courses to prepare you? Driven by a desire to protect the environment, John Willms, Stephen Garrod and Harry Dahme were three of the first in Ontario to practice what is now known as environmental law.

In 1970, they had to make it up for themselves.

The first tentative steps were taken by some law professors and their students at the University of Toronto (U of T). To support the newly-formed Pollution Probe and emerging environmental groups who were fielding calls from concerned citizens, they decided to establish a public interest law clinic. They thought perhaps the courts could be used to remedy the complaints that were coming in fast and furiously as concern for the environmental took hold. To this end, they created the Canadian Environmental Law Association (CELA), and in late 1971 a young lawyer named David Estrin became its first full-time lawyer.

John Willms, who had been at Osgoode Hall law school when the idea of an environmental law clinic began to percolate, was drafted into service by his former classmates as CELA’s Treasurer and member of their Executive Committee. As he became increasingly more involved with CELA’s legal work in a volunteer capacity, environmental issues started to become part of his private practice at the firm of Greenspan and Vaughan. Now in 2014 the firm, which evolved to Willms & Shier, is the largest environmental law firm in Canada. Stephen Garrod started as a student at Osgoode Hall Law School in 1974, enrolled in York University’s Masters of Environmental Studies program in 1975 and became the prototype for and the first graduate of York’s Joint LLB/MES program in 1978. Fresh out of law school, he found his first articling job with David Estrin after David had left CELA and opened his own practice, the first in Canada dedicated solely to environmental issues. After a few years of honing his legal skills with David, Stephen left to start his own practice in environmental law, in Guelph, which continues today as Garrod Pickfield LLP. Similarly, Harry Dahme, who was weighing whether he could make a greater impact through politics or law, chose law and, after graduating from Osgoode Hall Law School in 1982, replaced Garrod as David Estrin’s associate. A few years later, Estrin and Dahme joined forces with Gowlings, one of Canada’s biggest law firms, where in 2014 they celebrated 30 years of working together in the practice of environmental law.

Over the course of the forty years practicing environmental law, the three of them have seen significant changes in the legal landscape. In the beginning, their clients were local groups and environmental organizations fighting to protect communities from contamination or unwanted projects. Sometimes they got paid in homemade wine or chickens and sometimes they didn’t get paid at all. But those were heady days in which representing a citizens’ group might lead to significant progress – stopping toxic waste dumping, preserving agricultural lands or reforming the way the Ministry of Environment approved projects, particularly landfill sites. At that time, the Ministry’s certificates of approval, which were supposed to set conditions for how pollutants would be managed, were often like “elevator licences,” according to John Willms. However, the hard-fought battles that communities waged in courts or hearings led to tightening up the way in which landfills around the province were designed and monitored.

The first change in the practice of environmental law occurred when many of the clients who had cut their teeth as environmental leaders ran for municipal office. Once elected as councillors, they hired the same lawyers that had helped them in their fights with the Ministry. In some cases where municipalities were looking for landfills or to site new projects, the lawyers found themselves hired to represent the proponents of projects rather than the opponents, always with the goal of ensuring that projects met the highest standards for community consultation and environmental protection.

In another important development that influenced the evolving practice of environmental law, the 1980s saw the introduction in Ontario of new acts and regulations with far-reaching effects. The Environmental Assessment Act required detailed plans and reviews of projects before they could go ahead. If the projects were contentious, hearings might be held. At the same time, in 1988 the Intervenor Funding Project Act gave citizens’ groups the financial ability to hire environmental lawyers. Instead of time in court, environmental lawyers more often found themselves at lengthy hearings before boards such as the Environmental Assessment Board or the Ontario Energy Board where arguments over major project proposals could be heard and resolved. The years between 1985 and 1990 were a boom time and many large Bay Street firms set up departments that offered expertise in environmental law.

In the 1990s, however, the provincial structure that allowed for environmental reviews and hearings began to be dismantled. The Environmental Assessment Act was revised so that few projects were subject to hearings and the Intervenor Funding Project Act was not renewed. The practice of environmental law shifted again, and environmental lawyers today find themselves engaged in cases revolving around corporate due diligence, the rehabilitation of contaminated sites, proposals for energy projects, pits and quarries and environmental planning.