The Great Lakes form the largest group of freshwater lakes on Earth and 21% of the world's surface fresh water.

Great Lakes United: Cross-border coalition pushed Great Lakes issues onto political agenda

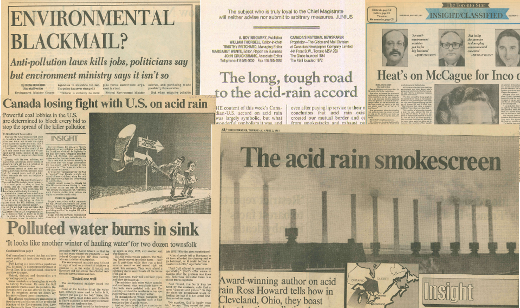

By the 1970s, the ecological fate of the Great Lakes hung in the balance. Lake Erie was choked with algae, toxic dump sites were leaking poisons into the Niagara River, and the media routinely featured graphic reports of fish kills and deformed waterfowl. Yet despite the mounting evidence, federal, provincial and state governments on both sides of the basin were ponderously slow to respond to the rapid decline of the Great Lakes.

Into that vacuum of leadership stepped Great Lakes United (GLU), one of the first and, in its time, one of the most effective cross-border environmental coalitions. In a series of well planned campaigns, delivered with passion and backed by solid research, GLU facilitated citizen action, lobbied politicians and other decision-makers on the looming environmental crisis, and offered practical solutions on issues threatening the ecosystem of the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River.

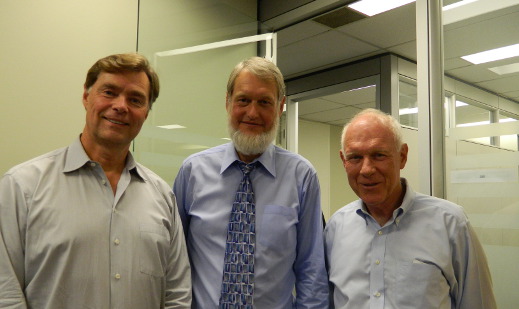

Three former Great Lakes United Board members – former Environment Canada and Toronto Public Health official

Jeanne Jabanoski, environmental activist and academic

John Jackson, and now retired Canadian Environmental Law Association researcher

Sarah Miller – discuss the early days of the organization and the evolution of environmental issues over the last 35 years in the Great Lakes basin. John also served as GLU’s president and vice president, Sarah as its vice president, and Jeanne as its Canadian treasurer for two terms.

The Beginning

In May 1982, a diverse group of conservationists, environmentalists, trade unionists, First Nations reps, educators and scientists from Canada and the United States gathered for two days in a sunlit meeting room on Michigan’s Mackinac Island to find a way to work together and focus attention on some of the key issues facing the Great Lakes. A new binational coalition was officially launched six months later during an organizing meeting in Windsor, Ontario. Great Lakes United – a name chosen after hours of debate – reflected the members’ overriding desire to work together for a common cause, while the witty acronym GLU represented “the group that holds the Great Lakes together.” By 1984, some 100 groups had gathered under the GLU banner.

The coalition first coalesced around its members’ opposition to an ambitious and environmentally invasive proposal by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to open the Great Lakes, via the St. Lawrence River, to winter shipping. Concerned by the destructive impact of ice breaking on fish and wildlife habitat and the increased risk of spills, GLU succeeded in persuading the U.S. Congress to shelve the project in 1984.

Early success

That early success was followed by a series of effective, well planned campaigns that are still remembered for their inventive tactics. For instance, GLU co-hosted a “toxic buffet” for Washington, D.C. decision-makers featuring a menu of lake-caught salmon, trout and sturgeon – each with its toxic contaminants listed – and drinking water sourced from each of the Great Lakes. The deformed cormorant Cosmo, its beak twisted and distorted by the mutagenic chemicals in its parents’ diet, made several memorable appearances at press conferences in the Region and congressional hearings in Washington DC. In 1986, GLU toured communities around the lakes, holding high-profile community hearings where local residents voiced their concerns about environmental issues and toxic threats. The findings from GLU’s hearings became an important basis for the Canadian and U.S. governments’ renegotiation of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement in 1987.

Again and again, GLU’s reasoned arguments and impassioned campaigns derailed major water diversion proposals, focused attention on the toxic effects of air and water pollution on wildlife, supported passage of the

Great Lakes Charter on water diversions and the

Four-Party Niagara River Toxics Management Agreement, and helped strengthen the U.S.

Clean Water Act. GLU staff also worked with local groups to build support for the development of Remedial Action Plans (or RAPS) for the then 42 areas of concern in some of the most contaminated sites around the basin, and successfully lobbied for the addition of a 43

rd site to this action list.

Debate continues over tactics

By May 1986, GLU’s member groups totaled 200. However, despite the early and on-going effectiveness of GLU, members continued to debate whether the organization should embrace political action by mobilizing and coordinating grassroots advocacy, or whether it should be a looser coalition, focused on education and information sharing.

“GLU's success was the care they took to be inclusive and democratic. I remember a lot of hard work that aimed for consensus on the principles that would guide campaign programs and actions each year.” — Sarah Miller

In the end, GLU adopted a compromise approach, supporting and facilitating the campaigns of local groups, while giving voice to those community concerns on the basin-wide international stage. In turn, the exuberance and local expertise of the grassroots groups kept GLU on the cutting edge of environmental developments. For example, GLU and its membership pioneered the ‘ecosystem approach’ and the ‘zero discharge’ goal. They insisted that Great Lakes governance needed to be guided by these concepts.

As a result of the success of its community hearings on Great Lakes issues in 1986, GLU was granted official observer status during the formal negotiations between Canada and the U.S. on the 1987 update of the

Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement (

GLWQA)

. And when GLU talked, politicians listened because they knew the coalition was backed by hundreds of organizations with tens of thousands of members.

Working with the IJC

GLU also played an integral role in the deliberations of the International Joint Commission (IJC), the independent binational body established by the U.S. and Canada to regulate shared water uses and investigate transboundary issues. The biennial IJC meetings in the 1980s and early 90s provided a platform for GLU to raise concerns, often loudly and boisterously, about contaminated sediments, human health effects, invasive species and climate changes effects on the Great Lakes, and to push for the ‘zero discharge’ of priority pollutants to both the Commission and the international media.

However the terms of the 1987

GLWQA, assigning operational responsibility for much of the action on the Great Lakes back to the individual federal, state and provincial agencies, undermined the influence of the IJC and, ultimately, binational coalitions like GLU. The organization continued to work and contribute to the environmental discourse, but the binational Great Lakes community of governments, scientists, and activists was weakening.

Funding foundations moved on to embrace other causes, while government funding for citizen participation evaporated. The renewal and modernization of the

GLWQA – the focus of so much of GLU's work – was put ‘on hold’ for almost 10 years. The Canadian federal government quietly abandoned its Great Lakes commitments, while the U.S. funded local agencies to carry on their Great Lakes projects unilaterally.

These changes in the Great Lakes activities and community made the challenge of maintaining the binational coalition of Great Lakes United ever more challenging. GLU’s Board of Directors made the difficult decision to close down the organization’s operations and Buffalo office on July 1, 2013.

Although individual former GLU members remain active, they sorely miss the coordinated international voice that GLU provided for the Great Lakes.