In the 1980s, environmental activists suspected that their concerns would be resolved faster if they had better access to the justice system. The Environmental Bill of Rights was designed to provide that.

In the 1980s, environmental activists believed that their concerns would be resolved faster if they could initiate their own legal actions. Lawyers at the

Canadian Environmental Law Association proposed a law called the Environmental Bill of Rights that would give citizens greater access to the justice system. Over the years, many opposition politicians in the Ontario Legislature introduced a version of this bill, but none were passed. Finally, in the 1990 election, the New Democratic Party made passing the bill part of their election platform. After they were elected, an

Environmental Bill of Rights (EBR) that included some of the original features of these first bills was passed. The

EBR has since become one of the province’s signature pieces of environmental legislation.

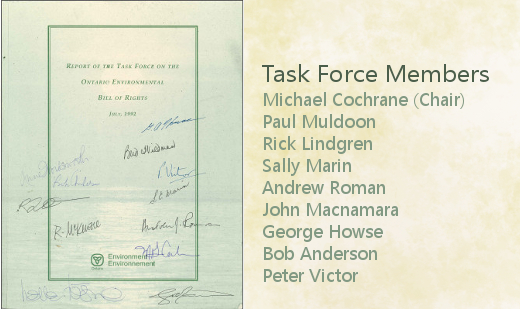

It is important to recognize both the people who helped create the

EBR and those who helped implement it. In 1990, the then-Minister of Environment, Ruth Grier, appointed a task force that included representatives of the environmental and business communities and of the government. They were asked to develop the

EBR based on a number of principles:

- the public's right to a healthy environment;

- the enforcement of this right through improved access to the courts and/or tribunals, including an enhanced right to sue polluters;

- increased public participation in environmental decision-making by government;

- increased government responsibility and accountability for the environment;

- greater protection for employees who "blow the whistle" on polluting employers.

Michael Cochrane, who was a lawyer with the Ministry of the Attorney General, in his role as chairman of the Task Force on the Environmental Bill of Rights, led the Task Force through a series of meetings and often difficult discussions. The EBR Task Force included Paul Muldoon from Pollution Probe and Rick Lindgren from the Canadian Environmental Law Association; Sally Marin, a lawyer from the Ministry of Environment; Andrew Roman, a lawyer from Miller Thompson; and John Macnamara, George Howse and Bob Anderson, who represented different business associations. (John Macnamara, who is participating in this session, represented the Ontario Chamber of Commerce.) Peter Victor, who also contributes to this session, was at the time the Assistant Deputy Minister of Policy in the Ministry of Environment, and was responsible for rolling out the provisions of the

EBR.

The Task Force’s work

To begin their innovative work, Task Force members started with the principles that were given to them by the Minister. Over the course of several months and many meetings, they discussed various ways to deliver these principles through the EBR.

One of the most contentious issues was enhanced access to the courts and a citizen’s right to sue polluters. The environmentalists argued that citizens should have the right to sue polluters if provincial environmental laws were not being applied or enforced. Businesses worried that they’d be harmed by an

EBR that gave citizens an unrestricted right to sue. The Task Force eventually agreed to open up legal avenues to the public. Citizens have the right to apply for leave to appeal certain Ministry decisions such as permits or licences or to apply for reviews of existing environmental laws. Citizens were also given the right to apply for an investigation of any violation of an act, regulation or instrument and the right to sue a polluter for causing environmental harm to a public resource.

Technology and the EBR

Another

EBR goal was the right for the public to participate in environmental decision making in the province and to have greater access to information. The solution that the Task Force proposed was an Environmental Registry where people could be notified about important laws and policies proposed by the government. However, this was accomplished in a way that the

EBR Task Force couldn’t have anticipated at the time.

The first electronic registry was developed by staff of the Ministry of Environment who trained librarians across Ontario to provide members of the public with access to this

EBR ‘bulletin board’. Then, as personal computers increased Internet access, new opportunities for sharing government information dovetailed with the aspirations of the

EBR. Today, the

Environmental Registry is a website where every Ontarian has the right to comment on proposed provincial environmental laws and regulations. Ministries must post certain proposed environmental laws and regulations for public comment. The Ministries’

Statements of Environmental Values are also posted on the registry.

As well as developing the Registry, dedicated civil servants within the Ontario public service played a critical role in setting up the infrastructure underlying the

EBR, coordinating its activities across the government Ministries covered by the legislation and ensuring the Act’s success. In addition, Ministry of Environment staff were instrumental in extending the application of the

EBR from the 4 Ministries proposed by the Task Force to the 13 now governed by the legislation.

Another provision developed by the Task Force was protection for workers reporting environmental violations in their workplaces. If someone

"blows the whistle" on the unsafe environmental practices of their employer, they are protected under the

EBR. It sounds fair and simple today, but before the

EBR was passed in 1993, these environmental rights were not the law of the land.

In order to meet the principle of making the government more accountable and providing oversight of their environmental activities, the Task Force proposed the appointment of an independent Environmental Commissioner. When the legislation was accepted, a new office of the Environmental Commissioner of Ontario was created and run by staff of the Ministry of Environment until the first Commissioner was appointed. The current Commissioner, Gord Miller, developed this

Environmental Beginnings series to commemorate the roots of environmentalism in Ontario and the pioneers in the movement.

The thoughtful, systematic work of the

EBR Task Force and its successful implementation by Ontario public servants involved gave citizens an

Environmental Bill of Rights that has endured for 20 years, through several changes of government — continuing to make sure that Ontarians have the right to be involved in making sure our environment is protected.