As designated environmental reporters in the 1970s and 80s, Howard, Israelson and Keating played a critical role in conveying information gathered from academics, scientists, governments and non-governmental organizations to the public.

“GLU's success was the care they took to be inclusive and democratic. I remember a lot of hard work that aimed for consensus on the principles that would guide campaign programs and actions each year.” — Sarah MillerIn the end, GLU adopted a compromise approach, supporting and facilitating the campaigns of local groups, while giving voice to those community concerns on the basin-wide international stage. In turn, the exuberance and local expertise of the grassroots groups kept GLU on the cutting edge of environmental developments. For example, GLU and its membership pioneered the ‘ecosystem approach’ and the ‘zero discharge’ goal. They insisted that Great Lakes governance needed to be guided by these concepts. As a result of the success of its community hearings on Great Lakes issues in 1986, GLU was granted official observer status during the formal negotiations between Canada and the U.S. on the 1987 update of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement (GLWQA). And when GLU talked, politicians listened because they knew the coalition was backed by hundreds of organizations with tens of thousands of members.

“[Through the 1980s,] environmental grant-giving was a mostly haphazard, ad hoc use of funds … The money ended up, in [too] many cases, in the wrong places at the wrong time.”By the 1990s two things were becoming clear. First, environmental groups desperately needed more (and more sustainable) funding to maintain their advocacy work, especially in the face of austerity-minded and business-friendly governments busy rolling back their environmental programs. And second, the foundations needed to start working together in order to make their donations more strategic and much more effective. It was becoming increasingly difficult to see how all the individual grants fit into the larger picture. In 1995, representatives from a dozen foundations initiated the idea of a network of Canadian environmental grantmakers that would collaborate, share knowledge and work together to build an environmentally sound and sustainable future for Canadians. The Canadian Environmental Grantmakers’ Network (CEGN) opened an office in October 2000, and incorporated federally as a not-for-profit organization in 2001. Canadian foundations also supported the Sustainability Network to help environmental groups and other non-profits improve their management, leadership and organizational skills. Over the last ten years, foundations have been a central force in resurrecting a series of progressive land use initiatives. Sparked by the Walkerton drinking water tragedy, provincial governments began to reconsider their slash-and-burn approach to environmental protection. First, the Harris government brought in legislation to safeguard the Oak Ridges Moraine from urban development. Then, the McGuinty government, backed by the solid research and an extremely effective public relations campaign prepared by a coalition of environmental groups, brought in legislation to protect more than one million additional acres in a Greenbelt that extends from the Niagara Escarpment through the Moraine lands and north to the shores of Lake Simcoe.

“The foundations all brought not only money, but a spirit of wanting to get something done.Today, foundations and funding programs are more important than ever, creating coalitions, forging partnerships, bringing new ways of thinking to the evolving environmental issues of the new millennium. Targeted donations are helping spark the green economy and building bridges between health professionals and environmentalists looking at the insidious impacts of toxics in the environment. The CEGN has grown to represent more than 65 private, community, public and corporate foundations, as well as government and corporate funding programs that provide over $50 million in environmental grants across Canada each year. Governments and large corporations have set up a number of funding projects to support environmental programs and objectives. For more information, see the Canada Revenue Agency webpage. For more information on many of Canada’s environmental grantmakers, visit the CEGN website at http://www.cegn.org.

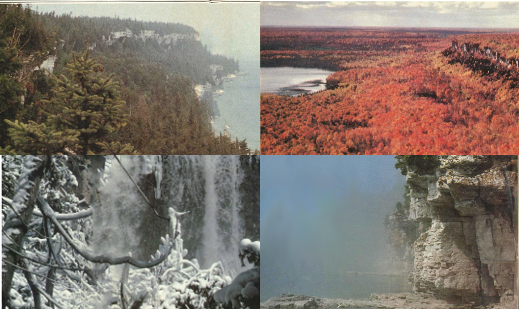

It was so dramatic. [The wastes in Love Canal] literally destroyed the neighbourhood ... [There were] swing sets, pools in the backyard – it could be your neighbourhood – literally melting in this toxic pool.On May 21, 1980, US President Jimmy Carter declared a federal health emergency and, in several phases, residents were evacuated from more than 900 homes in a 10-block area surrounding the canal. The notoriety of the Love Canal spurred the passage of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) in 1980 and the establishment of the Superfund remediation program which expanded to cover the excavation and containment of hazardous wastes leaking from hundreds of abandoned dump sites across the US. The Love Canal disposal site was covered by a synthetic liner and clay cap and surrounded by a barrier drainage system. Contamination from the site is still being controlled by a leachate collection and treatment facility. While the New York State Health Commissioner eventually allowed 250 of the abandoned homes to be resettled, hundreds more were demolished and a 16-hectare portion of the site remains empty and overgrown, locked behind security fences to this day. In September 2004, the Love Canal was removed from the Superfund’s National Priority List (NPL). Hyde Park, the “seeping giant” While the Love Canal got most of the headlines, Hooker Chemical continued to dump another 72,600 tonnes of chemical waste – four times more than what went into Love Canal – down the road into the six-hectare Hyde Park Landfill from 1953 to 1975. These were, primarily, chlorobenzenes, toluenes, halogenated aliphatics, and 2,4,5-trichlorophenol still bottoms. While all these compounds pose a serious threat to human health, the still bottoms were contaminated with up to 1.45 tonnes of dioxin, widely acknowledged as one of the most toxic chemicals known to science. That made Hyde Park the single largest deposit of dioxins in the world. And those dangerous chemical wastes were not staying put. Some 600 metres to the northeast of the site, the Niagara River flows north towards Lake Ontario, the primary source of drinking water for millions of people on both sides of the border. The ominously named Bloody Run Creek flowed through the landfill, then under a neighbouring industrial property and through a storm sewer that emptied into the Niagara Gorge. In addition, contaminated groundwater moved through both the glacial overburden and the heavily fractured dolomite bedrock outwards and downwards towards the Niagara Gorge. In 1979, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sued Hooker Chemical to force the company to remediate the site. Two Canadian environmental groups – Operation Clean Niagara and Pollution Probe, both represented by the Canadian Environmental Law Association (CELA) – intervened as amici curiae or “friends of the court” in the federal district court that hammered out and ratified the private settlement agreement between the company and the EPA in April 1982.

Hyde Park was just one [of hundreds of toxic waste sites in the Niagara Frontier], and perhaps one of the less really scary ones in a sense – it was in a hole in the ground and partly contained. There were others that were literally on the banks of the [Niagara] river.The Hyde Park site was listed on the NPL in September 1983. An aquifer survey, completed that year, defined the extent of contamination and a final remedial action plan was approved by the court in 1986. To date, a landfill cap installed in 1994 has decreased leachate generation, more than 1.1 million litres of dense oily liquids and some 23,000 cubic metres of contaminated sediment have been removed and treated, and purge wells have been installed to contain contaminant plumes and prevent wastes from seeping into the Niagara River. Operation and maintenance of the groundwater removal and treatment systems will continue for the next 30 years. The Hyde Park case sparked a lot of political interest at both the federal and provincial levels, as well as the development of some analytical tools still used today to track minute amounts of extremely toxic chemicals through the environment.

There was quite a mobilization of resources in Canada from a scientific and technical point of view. The Canada Centre for Inland Waters in Burlington … developed some really innovative research techniques for managing [tracking and monitoring] very small amounts of toxic chlorinated types of compounds.The Hyde Park Landfill file is still active Today, most of the chemical wastes buried across the Niagara Frontier are still lying in the ground, with the capacity to remain toxic for hundreds of years, if not forever. In September 2012, CELA on behalf of the cross-border environmental coalition Great Lakes United wrote to the Emergency and Remedial Response Division of the US EPA to oppose the deletion of the Hooker Hyde Park Superfund site from the National Priorities List. While deletion from the NPL does not preclude the EPA from conducting additional waste “removal” activities at the site, the Agency would be barred from conducting more extensive “remedial” activities, such as such as groundwater treatment. According to CELA counsel Joseph F. Castrilli, “Many of the key reasons that necessitated Hyde Park being listed on the NPL in the 1980s continue to exist today. The chemicals are still there, they are still hazardous and, because of the remedial action strategy chosen, they require robust environmental management essentially forever.” For those reasons, Great Lake United opposes the deletion of Hyde Park from the NPL.

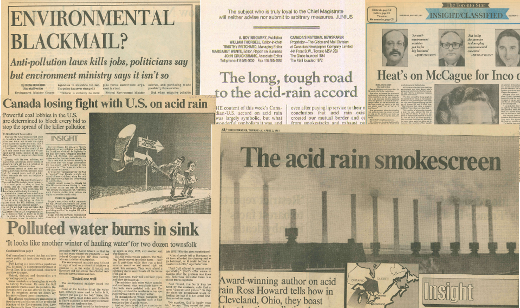

I remember fights in [the district manager]'s office ... The door was closed and you'd hear screaming, then you'd hear things hit the wall. This was what it was like there. It was a circus.The Temagami story begins with Hap Wilson: canoeist, outfitter, artist, environment enthusiast, and author of many wilderness guidebooks. As a park ranger from 1976 to 1984, Wilson surveyed and published Temagami’s first, and very popular, Canoe Routes guidebook. This helped lead to a greater awareness of the need for wilderness protection, and opened up the area to outsiders who became advocates through discovery. However, logging and road building were still allowed. Things heated up when a district manager from MNR started illegally clearing land for the Red Squirrel Road in the fall of 1984. Hap was the first to learn about the road clearing, and quickly worked with his supervisor, Reg Sinclair from the Ministry of Natural Resources to "block" particular logging operations scheduled for critical areas by designing hiking trails or new canoe routespushing the development into the review process. In July of 1985, environmentalist Terry Grave and lawyer Owen Smith requested an Environmental Assessment (EA), and lobbied it hard through Queen’s Park for three months. In September 1985, the government finally agreed to conduct the EA. One year later, it was released, but the government had altered the document and removed the author’s name, making it unusable. Nevertheless, the EA was critical to delaying logging and building of the Red Squirrel Road, and gave time for Terry, Hap and activist Brian Back to get organized. In 1986, they formed the Temagami Wilderness Society, with the mission to keep Temagami wild. One of the first things the Society did was to identify a reason for preserving the wilderness in Temagami. In 1988, they commissioned Peter Quinby, a forest-ecology doctorate, to study the Temagami forest. Quinby confirmed the existence of old growth in Temagami – endangered from logging in Eastern Canada. With their cause strengthened by this finding, the Temagami Wilderness Society distributed brochures featuring photos of Temagami, brought people to the area, and campaigned to stop the area from being developed. For several years, the Temagami Wilderness Society did their best to stop the logging of old growth, working hard at public relations and fundraising. However, nothing seemed to stop those who were determined to build the road. In 1989, the government resumed building the Red Squirrel Road through the newly developed Lady Evelyn-Smoothwater Wilderness Park. Finally, the Society decided to set up a blockade at the Red Squirrel Road, the first of its kind in Eastern Canada. You can see the photos of the blockade in the photo section of this story. Today, Temagami is one of the remaining wilderness canoeing areas in the world, as logging and development continue to endanger these precious areas. In Ontario, we are lucky to have legislation and environmental groups to protect these precious landscapes and ecosystems. It is important for the next generation to keep it that way. Listen to the story to learn about the blockade, how Brian Back was buried in the ground, how former Ontario Premier Bob Rae (leader of the opposition at the time) was arrested, and learn what happened to Temagami and the Temagami Wilderness Society.