In this session, Bob, Doug and Mark discuss the political upheavals in Ontario and the influence of environmental activism on governments of different political stripes.

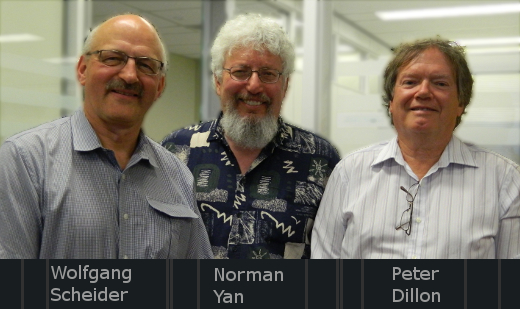

Robert Paehlke, Doug Macdonald and Mark Winfield have all been well-placed observers of, and sometime participants in, Ontario’s environmental history. As educators, they have taught and written about the events and the policies that have shaped Ontario’s environmental path. As well, working for or in association with non-governmental organizations, they have themselves influenced the province’s decision-making process.

Robert (Bob) Paehlke is a professor emeritus of Trent University, where in the 1960s as one of a newly-minted group of environmental professors, he taught environment and politics and continued to do so for more than 35 years. In 1971, he founded Canada’s premier environmental magazine, Alternatives, which has been an invaluable source of scientific information and policy discussion ever since. He is also the author of numerous publications on environmental issues including his most recent book,

Some Like It Cold: The Politics of Climate Change in Canada.

Doug Macdonald has taught environmental policy at the University of Toronto (U of T) for several years as a Senior Lecturer in the School of the Environment. Before coming to U of T, he was the Director of the Canadian Environmental Law Research Foundation from 1982 to 1988, which was renamed the Canadian Institute for Environmental Law and Policy (CIELAP) but is now defunct. He has also written extensively on the need for a strong environmental assessment process in Ontario.

Mark Winfield is an associate Professor at York University’s Faculty of Environmental Studies, the first environmental program in Canada. He specializes in environmental policy, sustainable energy and urban sustainability. Before coming to York, he was Program Director at The Pembina Institute from 2001 to 2007, and before that Director of Research for CIELAP. In 2012, his book,

Blue-Green Province: The Environment and the Political Economy of Ontario, examining the relationship between environmental policy and the politics and economy of the province, was released.

In this session, Bob, Doug and Mark discuss the political upheavals in Ontario and the influence of environmental activism on governments of different political stripes.

The Conservative Years and the Response to Environmental Concerns

In the late 1960s when environmental activism began, Bob Paehlke recalls small groups popping up in every city and town in Canada, and even a minor protest could attract publicity. Then, during the 1970s and early 80s at the same time the environmental movement was gaining strength, the Conservative Party was enjoying a long uninterrupted run of governing the province. The government under Premier Bill Davis responded to growing environmental concerns by establishing the

Ministry of Environment in 1971. This was accomplished by piecing together institutions such as the Ontario Water Resources Commission and departments from other Ministries that had responsibility for air, water or land. Also in 1971, Davis broke with the institutional model and, in an act of goodwill towards the nascent environmental momentum and the Stop Spadina Save Our City campaign, cancelled plans for the Spadina Expressway. Spadina was one of six expressways intended to bring suburban commuters to their jobs in downtown Toronto that would have meant the destruction of thousands of homes in the heart of the City.

One of the boldest initiatives, though, of the Davis government was the introduction and passage of the Environmental Assessment (EA) Act, which established an innovative planning process for public projects. It was intended to provide for “an integrated consideration at an early stage of the entire complex of environmental effects which might be generated.” It was passed by the Ontario Legislature in 1975 and proclaimed in force in 1976. According to Mark Winfield, the EA Act transformed the Ministry of Environment from a Ministry concerned about pollution and garbage to a Ministry that could pass judgment on the desirability of projects proposed by other Ministries and government agencies such as Ontario Hydro. From an institutional perspective, it was a huge shift that saw the Ministry of Environment’s stature rise within government, from “a patched together Ministry to a Ministry with power.”

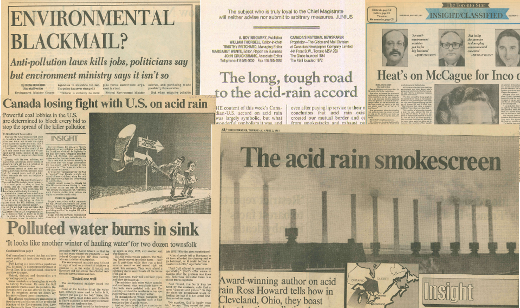

The Liberals’ Countdown Acid Rain Program: The Zenith of Activism

In 1985 after Davis’ retirement, although the Conservatives won more seats in the Ontario Parliament by a slim margin, they did not have a majority. Shortly after the election, the New Democratic Party agreed to support the Liberals for two years in return for the implementation of a mutually approved Accord. At this point, the momentum for controlling acid rain had been growing and in 1986 Environment Minister, Jim Bradley, introduced Countdown Acid Rain, an ambitious program that would limit the emissions of Inco and other major sources of sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides in the province. Environmental groups, particularly the Coalition on Acid Rain, had been instrumental in galvanizing public support for controls, and the introduction of this program reflected their considerable influence on the political agenda of the day.

During the late 1980s and into the early 1990s, with public support still strong and effective groups actively promoting an environmental agenda, the Ministry of Environment led by keen Ministers of Environment enjoyed a period of successful initiatives and policy measures. Many projects were reviewed under the Environmental Assessment Act with the public actively engaged in the planning process. The Ministry of Natural Resources, for example, under the Environmental Assessment for Timber Management was required to submit its plans for forest management to an extensive public review which started in 1985, and a decision to accept the EA with conditions was made by the Environmental Assessment Board in 1994. The Ministry’s enforcement activities were having a systemic impact on the way in which industry managed their environmental impacts. The Investigations and Enforcement Branch was actively bringing polluters to justice, and its successful prosecution of Bata Industries showed that officers and directors could be liable if they did not follow through on their environmental responsibilities.

The Legacy of the NDP

Another election in 1990 brought in the

New Democratic Party. Continuing a proactive approach to environmental concerns, Ruth Grier, the Environment Minister, banned incineration and took on the ill-fated task, which the former Liberal government had begun, of finding a site for Toronto’s garbage. The NDP also

introduced and passed the

Environmental Bill of Rights, which Mark Winfield describes as a part of the NDP legacy that has survived. However, the NDP were presented with tough economic times in the province and the Ministry of Environment, which had seen its funding go steadily up during the

Bradley years, was caught in the financial restraints being imposed by the government. This was the beginning of the Ministry’s funding and influence being eroded as successive governments continued to reduce the Ministry’s funding and weaken programs and legislation such as the EA Act that had been put in place by their predecessors.

The story of the environment in Ontario is not one of uninterrupted progress, say the historians. There were policy failures such as the Ontario Waste Management Corporation’s unsuccessful search for a hazardous waste site. And, after many of the gains realized in the decades of the 70s, 80s and into the early 90s -- the creation of the Ministry of Environment itself, the passage of strong environmental legislation and the aggressive work of the Investigations and Enforcement Branch -- the province’s once strong environmental performance has been diminished not only by the withdrawal of funding for the Ministry but by policy reversals and deregulation.